433 km flight – 28th June 1984

In the early 1980s, a new generation of glider became available, promising a quantum leap in performance because of the carbon fibre construction, which allowed longer and thinner wings than had been possible with glass fibre. After more than a decade of flying in the trusty Kestrel 19m, both in Ireland and in the USA, in the spring of 1984 I was awaiting delivery of a syndicated Nimbus 3, whose vocation was mainly to fly the Appalachian ridges of the eastern US.

But this particular form of the sport requires spring or autumn weather, the eastern US summers rarely being any good for it. So it was agreed that I would bring the Nimbus to Ireland for three months before it left Europe. I wanted to make the most of the opportunity, and if possible fly the first 500 km flight in Ireland.

Indeed, I wanted it to be a record flight, for which the rules are fairly strict. It could not be flown straight-out – the island is simply not big enough. And from Gowran Grange the few points on the west coast that are far enough away for an out-and-return would be nearly impossible to escape from, even if one could get to them in the first place. But a triangle does fit in, though the smallest side had to be at least 28% of the total distance.

In the UK, due to restricted space, they had adapted this rule, allowing triangles with a smallest side of 25%, but the question had never come up in Ireland till then. So to respect the 28% rule, I chose a triangle of 505 km, with a first leg from Gowran Grange to Boyle, Co. Roscommon. The longest leg was to be from Boyle to Fermoy, Co. Cork, and the last a return to Gowran.

On the day, the forecast had been collected from Baldonnel by the celebrated John Williamson, over from England to do a lead-and-follow cross-country course with pilots from both Dublin and Ulster clubs; and it predicted excellent conditions. Unusually so in fact, enough to encourage me to fill the Nimbus’s outer wing panels with water, bringing the all-up-weight to 665 kg.

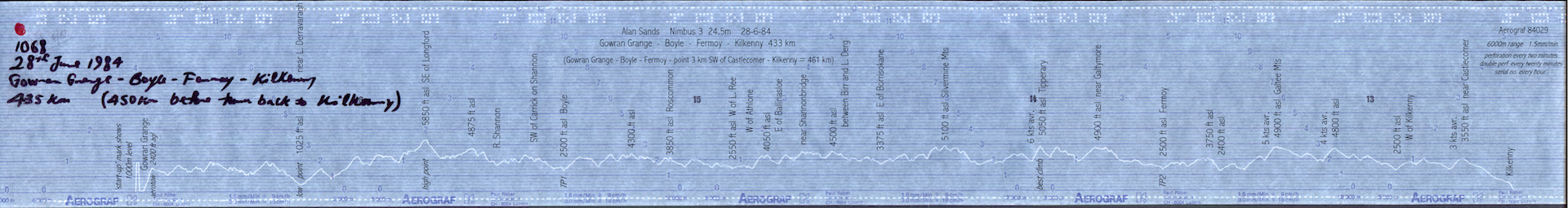

The Super-Cub’s 180 hp got us both over the hedge with a foot or two to spare and I set out on track at once, finding a first thermal north-west of Naas. The first fifty kilometres were flown between 2000 and 3500 ft asl and with a best climb rate of about 4 kts, but around Mullingar there are a number of fair-sized lakes, and it was the need to cross this area which caused the first difficulty.

From my recollection of the shape I believe that Lough Derravaragh was the culprit, killing the thermals stone dead on its downwind side. I had under-estimated the danger area and had gone too close – it was simply too early in the day to be in a low wet area. In ten minutes I lost well over 2000 ft and was soon down to 1025 ft, just 700 ft above the ground: I had to dump the water ballast to stay airborne.

When the Nimbus’s four 85 kg ballast tanks are filled (permissible for a glider in the US ‘experimental’ category), it becomes a missile: but with all of them empty it is a feather. It was this invaluable trait which allowed me to escape, and once away from the grasp of the lake, I was able to climb again. Flying rather carefully after this close call, I continued towards the turnpoint. And although the next two thermals gave only a little over 2 kts, within about forty kilometres I could see the other side of the coin with a climb to 5850 ft, the highest point of the flight, a little to the south-east of Longford.

Even though I had to fly thirty kilometres or so over the even lower flood plain of the Shannon I had no further difficulty in reaching the turnpoint. Boyle is just thirty kilometres from Sligo Bay, so inevitably the cloudbase became lower as I approached, and was little above 2500 ft by the time I got there. From Boyle I could see the far-off water of the Atlantic between the cumulus clouds, deep blue under a bright sun.

Quickly turning my back to the sea, I set out for the second turnpoint, almost due south and more than two hundred kilometres away. The cloudbase became higher again over the next twenty five kilometres, with a high of 4300 ft for this part of the flight. Towards the lower ground in the middle of the country it went down again, giving a low of 2550 ft as I flew to the west of Lough Ree. Indeed for the greater part of the second leg I did not climb much over 4000 ft, in a few 4 kt thermals and rather fewer of 5 kts.

Although conditions were never really strong, there were no real problems either, and I much regretted the loss of my ballast, which would have helped me to fly a good deal faster. I overflew the counties of Roscommon, Tipperary and Limerick, with brief incursions into Galway and Offaly. South of Athlone, I could see from time to time the peat cutting machinery working far below to produce Ireland’s energy – and this area produced some good thermals as well, although the thirty kilometre stretch east of Lough Derg put paid to these and produced another low below 3400 ft.

Things improved over the higher ground to the south, starting with a climb to 5100 ft over the Silvermine mountains, and after another lowish patch over the valley of the Mulcair River, which meanders down to the Shannon at Limerick, I found the one 6 kt thermal of the flight, which took me back above 5000 ft again. And then came Co. Cork. Fermoy had seemed like a useful turnpoint, easy to find and in the approximate position I needed when planning the task. But it is low-lying, and only thirty-five kilometres from the sea, so the sea-breeze from the south coast had had ample time to arrive there before I did, once again at 2500 ft.

Although it was soarable locally, I had great difficulty regaining enough height to fly across the Kilworth mountains to the north-east, which go up to around 650 ft even at their western end and which presented me with a broad expanse of fir plantations and other unlandable ground. I wasted half an hour or more in repeated attempts to get out of the bowl between them and the Nagles mountains to the south-west. It was this lost time which was going to cost me the flight.

I did eventually get back up to 3750 ft and made a break for it – to stay there could only have made for an outlanding anyhow. I admit to being nervous about a first land-out in such a large glider, but need not have been, as I discovered a couple of weeks later. The field just needs to be wide enough to avoid touching a wingtip – the airbrakes are highly effective, and the approach can safely be made at low speed. No doubt I should have taken this risk earlier, as by now it was a race against time, and the day was clearly past its best.

There were a couple more low points around 2400 ft before I was far enough inland to find a worthwhile thermal, which took me back up to 4900 ft, at an average of 5 kts. This thermal was near the Galtee mountains, and a second twenty minutes later went nearly as high, and averaged 4 kts.

Away from the high ground the thermals were already disappearing, although there was a weak one as I passed a little to the west of Kilkenny, on track for Gowran. Approaching Castlecomer there came a 3kt climb back to 3550 ft, but it was becoming clear from the dead sky ahead that to continue would mean a final glide towards Gowran. It would be a very marginal one too, with a field landing somewhere near the Curragh as the most probable outcome.

And I learned by radio that most of the other gliders on cross country had landed out, meaning that all available hands would be fully occupied for much of the evening. So I told the tow-pilot that I would go back to Kilkenny and land, and asked him to come and tow me back. On landing, I found that the entire leading edge of the wing had a rather puzzling thin black line along it – which turned out to be peat dust carried aloft by the unusually dry air on the second leg of the flight, by a fair margin the longest I ever had in thermals in Ireland.

The distance flown as far as Kilkenny was 433 km, although in going from Fermoy to within three kilometres of Castlecomer and then back to Kilkenny I had covered more than 460 km over the ground. With the aerotow retrieve, total flight time for the day was eight and three quarter hours, but I don’t remember being especially tired – nothing is more comfortable than a Nimbus !

In retrospect, I should have been less obsessed with records, and should have gone for an out-and-return flight from Bellarena, or for a flatter 500 km triangle out of Gowran. With the right choice of turnpoints, I think such a triangle could certainly have been completed on this particular day.

Of course nowadays one could choose a random point somewhere north-west of Fermoy and the GPS would find it and log it; but in those days one needed something identifiable for the turnpoint photo, not easy in a rather featureless band of country. And it may never be easy to complete a triangle from whose three corners one can see the sea …

Still, what’s done is done, and by mid October the Nimbus was on its way to the ‘States, where it did quite a few other epic flights. While it was in Ireland it flew over three quarters of the thirty-two counties, and I believe I caught a glimpse of nearly every one from it. It was well worth the trouble of bringing it there.

Alan Sands

2012

28th June 1984

Alan Sands

Nimbus 3 24.5m – 60:1 glide angle (with 170 kg water ballast on take-off)

Gowran Grange – Boyle, Co. Roscommon – Fermoy, Co. Cork – Kilkenny

flight time: 8 hours 10 minutes distance: 433 km

(Task declared was a 505 km 28% triangle, with Gowran Grange as the goal)